|

|

|

In Search of the African Banjo:

A Polyrhythmic Journey to Mali and Back Again

While on his musical mecca to Africa, Jayme Stone rarely let locals know of his accolades and burgeoning recording career in North America. He went to immerse himself in the high-spirited soundscapes, the daily life and lore of Africa. What he came home with was knowledge of two banjo ancestors never revealed before in the West, aspects of African music that eluded its American counterparts, and musical friendships that reach across continents.

“I played very little occidental music,” Stone recalls about his seven-week Malian adventure, “and was more intent on learning their craft. They thought I was some curious traveler with an ngoni that had gone through the industrial revolution. I ate with my hands out of communal bowls, braved the local transportation, and learned music on their terms.”

Though he began searching for the banjo’s surviving ancestors, the Canadian explorer became curious about what aspects of African music did not make it across the ocean with slavery. “The culture of slavery in North America, which nobody likes to talk about, was clearly not the best context for an authentic and meaningful cultural transmission of music,” Stone explains. “I wanted to find out how music is made on their turf.”

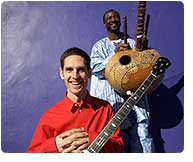

The fruits of this journey can be heard on Africa to Appalachia, a collaborative album with griot singer and kora player Mansa Sissoko. After two years of touring in Canada, the US and the UK and a Juno Award for Best World Music Album of the Year in Canada, the project continues to evolve and has Stone touring in 2010 with another Sissoko: Malian kora master and singer Yacouba Sissoko as well as fiddle phenom Mike Barnett, innovative bassist Brandi Disterheft and percussionist extraordinaire Nick Fraser.

This project was a long time in the making. An auspicious four years before setting foot on Malian soil, Stone met Mansa Sissoko, a griot singer and a unique voice on the kora (a 21 string African harp). Stone soon realized that Sissoko was a walking encyclopedia of Malian songs, many of them learned from his mother, a griot singer from the town of Baleya. “The griot is someone who is there to play the role of blood in the society, for the society to live,” says Sissoko. “He gives life to the society, musically, using carefully chosen words.”

“With little common language between us, we turned to music for communication,” Stone recalls of his first meeting with Sissoko. “This tangible heart-to-heart connection was there immediately and I knew that he was the perfect collaborator for the project. African music is not designed to be analyzed. It is learned by doing, by immersing yourself in the sound, rhythm and story. It is participatory. This quality has deeply affected my own relationship to music, compositional philosophy, teaching and audiences. I’ve become more attuned to the communal aspect of making music, particularly the powerful effect it has on our daily lives, emotional experience, sense of ritual and feeling of belonging.”

Stone also spent time with Mali’s premiere ngoni pioneer, Bassekou Kouyate, learning court music that dates back to the 12th century. One such song, “Bamaneyake,” sings the praises of N’dji Diarra, the once-king of Bambougo who ordered a canal to be dug from the Niger River to his village because his wife wanted to see hippos in her home town.

When not absorbing everything he could from elder musicians in Bamako, Stone could be found traveling rural Mali. Unlike most outsiders sealed safely in their Land Rovers, Stone and his guide Hamadi Traore lit out from Bamako on the overheated, overcrowded poky public bus. Snapshot: fifty travelers, forty seats, babies in aisles, and occasional stops for prayer and raw yams. They wended their way through Dogon Country, a millennia-old natural escarpment considered to be one of the geologic and anthropologic wonders of the world. “I was curious to go somewhere where I had never heard recorded music from,” Stone muses. “Every time we got to a village, I would ask if there were any musicians.”

Aside from a burgeoning tourism industry, this collection of electricity-less villages remains largely untouched by the modern world. They walked from village to village, sleeping on roofs, perusing local markets, and looking for music. And they found it, in an artisan village known as Ende, where the people made and played an instrument called a konou, a rudimentary two-string banjo-like contraption made of carved wood and goat skin.

“I was told that a generation ago, fifty people in the village might have played the konou,” says Stone, “and now there was only one person left: Seydou Gindou. A sharp and cultivated young man, Seydou played music, excelled in dramatics, and headed up a coalition to preserve his local culture as it had become threatened by the lure of tourist dollars. He had never listened to a radio nor left his village.”

The incessantly rhythmic music of the konou, Stone learned, is used to cue elaborate story-songs that tell time-honored tales that border on the mythic. There was one about a boy who, upon seeing the sky hanging low, reached up to grab a star to bring light to the village. The villagers all know to listen for a change in the konou’s rhythm to move to the next segment of the story. “The startling discovery for me was Seydou’s playing technique,” says Stone. “It was identical to the old-time banjo technique known as clawhammer, made famous by Pete Seeger during the folk revival. There we were, halfway across the world, seeing first-hand the unquestionable link between Africa and the banjo as we know it.”

Coming across banjo ancestors unheard of in North America was a profound metaphor for the depth of African music still unexplored by Westerners. But the countless hours Stone spent with musicians was where much of the real work lay. A tireless practitioner, Stone became lost in the swirling, overlapping rhythms of ancient melodies, with each revolution getting one step closer to the source.

Produced by David Travers-Smith (Wailin' Jennys), Africa to Appalachia features kora player and singer Mansa Sissoko with guest appearances by pioneering fiddler Casey Driessen and celebrated ngoni master Bassekou Kouyate. The album won the Juno Award for Best World Music Album of the Year in Canada.

|

|

|

|

|

|