|

|

|

Flamenco Rising:

Flamenco Rising:

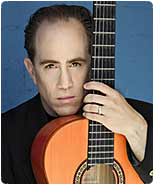

Chris Burton Jácome Reinterprets a Tradition in the Spanish Southwest

Sometimes it takes an outsider to innovate within a tradition. And sometimes that outsider is less outside than it appears. Flamenco guitarist Chris Burton Jácome is just that kind of outsider. His new album, LEVANTO (release: April 13, 2010), is a studio adaptation of an original full-length flamenco performance (dancers and palmas included) by CALO FLAMENCO, a touring music and dance ensemble based in Phoenix, Arizona. Few realize that the American southwest’s heritage from Spain and Mexico has led to a small but persistent flamenco legacy and following. Jácome is himself a son of Tucson, the scion of an old and pioneering family. His Mexican-born great-grandfather, a signer of the Declaration of Statehood for Arizona, begat his grandfather, a music lover who would take his daughters to the old Spanish shows that still ran in the Southwest in those days. Jácome is a musician whose own ascent has come on the wings of serendipity. A spark of revelation led Jácome to develop a new American tradition of classic flamenco brought to life on this wildly introspective CD.

Today, when Jácome performs his traditional flamenco, learned from members of musical gypsy families in Seville, Spain, he transports audience members to their ancestral past, real or imagined. But he is not fooling himself or his audiences into believing his music is rigorously authentic. When Jácome was young, he only wanted to be the next Eddie Van Halen. He was nineteen years old and living with his rock band when, one summer evening at five o’clock with the sun still high above the horizon, in his car on the road home, he experienced the phenomenon known as “love at first listen.” It was Gerardo Nuñez, and it was flamenco. “I was, like, ‘I have to play flamenco guitar!’ I walked in the door, and said to my band, ‘I quit. I don’t want to play rock music anymore. From now on, I’m a flamenco guitarist. I don’t know how I’m going to do it, but I will be a professional flamenco guitarist.’”

The passion took him. The years of coursework in college, where Jácome majored in Spanish Literature and Classical Guitar, almost prepared him to go to Spain. “I knew nothing about the flamenco culture,” Jácome admits, referring to the gritty, clannish lifestyle of gypsy flamenco musicians. “Spain was quite an eye-opener for me.” Yet, he was determined to learn, and fate kicked in to push him along. “When I jumped into that river, I felt like it just swept me away.” He took the first apartment in Seville that he could find on the Web and, by chance, his landlady, happened to run one of the main flamenco shoe stores in the city, providing plentiful connections in the flamenco world, which she generously shared. Soon, Jácome was backstage at shows, studying with masters, and drinking with gypsy legends in the Andalucían hills.

Early on, he found himself in a bar owned by the Farruco family, legends in the flamenco world. Jácome was awed and nervous, and his Castilian Spanish was still fumbling and slow. “I was so green, and I was so new, and I had no idea what was going on,” he remembers, echoing the words of culture-crossers throughout the ages. “I knew the importance and the weight of it, but I was so shy. I remember them all being so nice and so kind to me.” The good-hearted clan provided much encouragement, and Jácome soon became fluent in flamenco. “Flamenco is just like that: it’s a language, it’s a musical and dance language,” he reflects. No one could simply teach him how to play. Flamenco, he found, is acquired by osmosis, by living and breathing the art form. Today, those lessons have served Jácome well as he performs and tours throughout the country. In September of 2008, CALO FLAMENCO debuted LEVANTO in New York City to a sold out crowd. Jácome beams when he shares, “I couldn’t believe it when the stage-hand came backstage and told me there was a line around the block…I literally ran outside to take pictures! It was a dream come true!” Look for Jácome and CALO FLAMENCO to be performing in Idaho, Utah, Oregon, Alaska and more in 2010.

Jácome’s compositions would not be complete without Martín Gaxiola, his long-time friend and the artistic director of CALO FLAMENCO. The two met shortly after both returned from independent pilgrimages to Spain. In the small American flamenco community, they were attracted to each other’s dedication to tradition and innovation. “We just hit it off,” smiles Jácome. “Our personalities work really well together. He had the same respect for me and my art that I have for him.” He is the key to the entire show as it unfolds onstage, explains Jácome. “In flamenco, a dancer has to learn to conduct an orchestra. You have to tell that story so well that the accompanist, me, can read it. There’s a lot of improvisation that goes on, when the artists really ‘get’ each other, and Martín and I can do that. There is no doubt what he wants. When he moves, you know what he wants you to do. At least I do.”

In performance, CALO FLAMENCO employs dozens of dancers whose rhythmic footwork is as much a part of the music as of the spectacle. Turning the music, made to be animated by the company’s furious on-stage energy, into an album was a challenge. Instead of reproducing the live show, Jácome opted to present LEVANTO as flamenco music the way a classical album presents an opera, in movements and types of pieces. Each composition is original, which may count as a first in American flamenco. The production was also beset with the technical difficulties of recreating that live sound, particularly on the complicated “A mi hermana,” a song dedicated to Jácome and Gaxiola’s respective sisters, their companions in hard times. “In that piece alone, there are over twenty different tempo changes,” Jácome explains. “Start stop start stop. It was a logistical nightmare to record this. Live, everybody just follows everybody. It was really hard to make it sound natural on a recording… but we succeeded!”

Jácome, in writing the music on LEVANTO, held to the traditional flamenco style. Yet Jácome is confident that both traditionalists and newcomers will be satisfied with the results. He is conscious of audiences’ unfamiliarity with his art, but, instead of concocting contrived cover songs, Jácome reaches out. “I have way too much music in me, more than I can get out in my lifetime. Why should I channel someone else’s music instead of working on my own?” LEVANTO does not include the intimate dialogue with the audience that he holds in his own shows, but the songs are accented with American pop sensibilities. “I am always striving to create totally traditional-sounding flamenco,” he explains honestly, “but I come from a musical place so far removed from flamenco that, no matter how traditional I try to get, the result still sounds new and progressive. I have so many years in me of American music and being brought up as an American that I can’t just erase it.” Jácome’s individually authentic sound resonates with audiences from both sides of the Atlantic, always defying expectations.

That music is often tender, and frequently sad, in the style of most flamenco. Yet Jácome and Gaxiola, who worked closely together to write the show’s score, experiment with new images. “Conquistador” is in the style of a male dance, a farruca, but in the live show Gaxiola goes against tradition by highlighting this strong piece with women who perform onstage in men’s clothes. Gaxiola’s complex and thunderous footwork on LEVANTO speaks not of the hopeful ascent of a dove, as in the title track, but of conquest and the fight. Jácome and Gaxiola also chose to alternate soft solos and duets with roaring ensemble pieces, giving the show and the album space to linger.

LEVANTO, “I rise,” signals a new flight path for an old tradition. Jácome traveled far to discover his roots, back down the mountain and into the family fossil record (even discovering a “Jácome Chapel” in the cathedral of Seville). The warm rising air of the desert has propelled him again skyward, where the white-dove wings of his music can shine in the light of the sun.

<< release: 04/13/10 >>

|

|

|

|

|

|