|

|

|

The Childsplay of a Wily Old Timer, a Family of Fiddles, and a Visionary Inlaid Violin:

The Childsplay of a Wily Old Timer, a Family of Fiddles, and a Visionary Inlaid Violin:

Roots Music Band Tours East Coast in December 2010

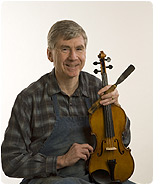

In a darkened room, under a bold shaft of light, fiddler and luthier Bob Childs beheld a violin inlaid with the image of a weeping boy. Awakened from this vivid dream, Childs was struck deeply—recalling his complicated childhood—and was compelled to find his voice at a crucial point in his life as a violin-builder.

Now Childs and his creations have fostered unexpected, playful friendships that inspired Childsplay, an ensemble based around Childs’s family of instruments and the shared richness of their voices. For more than two decades, the group has joyfully dug into everything from sprightly reels to poignant airs, from stony lonesome ballads to roots-infused rockabilly, on instruments that sing with the same soul, built by the same hands.

“Translating the sound that artists hear in their head to the violin is the challenge,” muses Childs. “Certain violins are like trumpets, bright and right out in front. Then there are violins like mine, that are darker, alluring, and pull the audience to the musicians,” be they a soloist from a world-class orchestra or a Celtic fiddle champ.

Listeners will feel this pull as Childsplay, whose latest album Waiting for the Dawn (Childsplay Records) features Crooked Still vocalist Aiofe O’Donovan, tours the East Coast in December 2010, including a gala performance at New York’s Symphony Space on December 3 at 8 PM. For these dates, the group will be joined by singer Mollie O’Brien, frequent guest on A Prairie Home Companion, and Irish and Appalachian-style step dancer Shannon Dunne.

As a boy, Childs spent several hard years in foster care before being adopted by a classical music loving couple. His family eventually moved to Maine, and Childs became enamored with the fiddle scene, teaching himself to play the old-time dance tunes he learned from elderly players. He worked his way through college by working with wood and “kept getting progressively smaller” in his projects, moving from house carpenter to cabinetmaker.

Then one day, early in his twenties, he met a wily old-timer of a fiddle maker, Ivie Mann, in the quiet town of Orrington, Maine. Childs took in his fiddle, a curly maple beauty handed down from a friend’s grandfather in Dublin, and wound up with an unexpected new vocation.

“When I first shook hands with Ivie, he literally shook my hand for fifteen minutes. I was actually kind of uncomfortable,” Childs recalls with a chuckle. “We went into his shop, and he said to come back in a week. When I went back, as I was walking out the door he asked when I was coming back. He pointed to his bench, where he had put out wood, and said, ‘I’ve been looking for someone to teach.’”

Childs avidly absorbed all the lore he could about Maine fiddlers and the art of violin building. He worked on his first instrument until it won the approval of a local string-playing elder, who gleefully played it for several hours. Childs soon coupled these powerful ties to tradition and traditional players with rigorous apprenticeships in the shops of world-class makers. He spent years in Philadelphia with Michael Weller, gaining insight into the centuries-old methods passed down from the great luthiers of Italy, Germany, and France, and coming into contact with his first Stradivarius and Guarneri violins.

It was toward the end of nine years as an apprentice, at a moment of doubt and hope, that Childs had his revelatory dream. “It was remarkable the way it happened. I had just finished the journeyman’s portion of my luthier training, when you get exposed to lots of instruments,” Childs recalls. “I was about to move back to New England to start my own business when I had that dream. It gave me the confidence to go forward in a very tough field. I was connected to why I was doing it.”

The connection Childs began to feel extended beyond his own past and passion and into his work with musicians who commissioned violins. He hears the timbre of timber, the final sound of an instrument in its raw materials, and can match the voice of a piece of wood to the spirit of the artist, while imbuing it with a unique voice.

“There’s something very mysterious about the violin that makes it special to be maker and player in today’s world,” reflects Childs. “You can’t really explain how a maker takes different pieces of wood from different trees, yet the instruments share a similar quality. It’s not the measurements or the varnish. It’s about the soul of the person.”

This soul sparked Childsplay, which got its start 26 years ago when a group of musicians all playing Childs’s violins asked Childs to sit in with them at a show in DC. Though Childs acts as artistic director, the individual musicians—all striking artists in their own right—compose and craft the pieces the ensemble takes on. “We come from all these varied musical traditions, from Ireland to Appalachia, from Scotland to Cape Breton, and everybody is out of their comfort zone,” Childs explains. “It makes for a very focused and creative working atmosphere and you just naturally open up a bit. That's what brings people back year after year: the process is very intensely creative and organic.”

Rollicking Slavo-Celtic dance tunes (“Liam Childs/Balkin’ Balkan/The E-B-E Reel”) intertwine with delicate traditional ballads and swaying instrumentals (“Soir et Matin”). The tender side of Elvis’s “Love Me Tender,” gently urged from the groups’ strings, contrasts with the wry grit of Steve Earle’s “Christmas in Washington.”

Boundaries between traditions and genres, between the conservatory and the kitchen party, break down in Childsplay, as players gather for a week of fellowship and hardcore rehearsal before every tour or recording session. The marathon music making has had some surprising results: unexpected friendships between musicians who share their appreciation for Childs’ instruments but diverge in their performance practices and repertoire.

All-Ireland fiddle champ Sheila Falls, for example, has struck up a powerful friendship with Boston Symphony violinist Bonnie Berwick that has led to collaboration outside Childsplay. These connections are about more than unexpected musical odd couples, however; they have shaped Childsplay’s distinct sound and familial spirit.

“Because everybody is so talented, over the years we’ve developed the tremendous harmony potential of our music but with very contemporary rhythmic sensibilities,” Childs explains. “It’s no longer ‘old’ or ‘old-fashioned music,’ but a sound that is alive and well. We have created our own voice as a group from years and years of performing together,” a voice that begins with resonant wood in the hands of a loving artisan.

|

|

|

|

|

|