|

|

|

Cuban Brass, Honey, and the Void:

Cuban Brass, Honey, and the Void:

The Sensual, Spiritual World of Pedro Luis Ferrer on Tangible

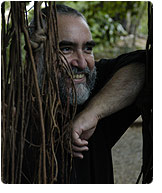

In the sheltered inner rooms of an old Havana house, an earthy philosopher plucks melodies and rhythms from the air and from Cuban music’s rich soil. Working alone or with close friends and relatives, he turns dances from the sugar cane fields and troubadour trills into magical realist declarations of liberty, as grandchildren dash in and out, and chicken grills out on the veranda.

This is the sensually philosophical world of Cuba’s maverick musician, Pedro Luis Ferrer, whose latest album Tangible (Escondida; March 29, 2011) continues the renowned singer-songwriter’s transformation of Cuban traditions into a vibrant cry for free thinking and intellectual liberation.

“When a human being is capable of conceiving the transformation of the surrounding world, an inevitable change begins. The spiritual world is as real as stone,” announces Ferrer.

Though roaming happily in the rarified realm of the spirit, Ferrer keeps his sound and his images firmly planted on traditional ground, drawing inspiration from the changüí of the mountains around Guantanamo, from the ballads of Cuban son, and increasingly on the brass arrangements of jazz masters such as Pérez Prado and Beny Moré.

Ferrer has long relied on guitar and the related Cuban tres as the rough yet resonant heart of his songs. Tangible adds brass sections and sinuous keyboards to Ferrer’s soulful vocals, skillful frets, and Latin percussion. The title track, “Tangible,” sparkles with bursts of horns, inviting listeners to dance while they consider God, innate love, verdant Reason, and the startling void. It’s a mix of the seen and unseen, the abstract and tangible, reflected in the music.

This shifting mix is Ferrer’s specialty. Ferrer, once a major figure in Cuba’s nueva trova of the 1960s, has created his own distinctive and dynamic palette of Cuban sounds, which he has dubbed changüisa, a feminine word playing on changüí and a pithy challenge to Latin musical machismo. It became a vehicle to engage tradition without slavishly following what Ferrer dismisses as “the old formula” in Cuban music.

“Changüisa is always changing,” Ferrer explains. “The concept of changüisa presupposes transformation. I created the term to describe the free intention to tackle tradition, the transformative intention. It assumes both closeness to the changui and to creativity, a concept that both unites and reconstructs traditions.”

Always questioning, always advocating new avenues for individual creative expression, Ferrer has been often marginalized in his home country. But there is no bitterness in Ferrer’s music. Instead, he makes a sultry, visceral call to life, with all its entanglements, its longing, its lingering kisses and disappointments.

Even in hymns to the power of human imagination, Ferrer sings of concrete experiences, of sights, tastes, and smells. He draws on his childhood love of Cuban folk poetry, often filled with quirky images and mangled metaphors, and his penchant for Dada-esque playfulness, even in the face of great truths. In “Te hablo de un país (I Tell You About a Country),” cityscapes merge with the aroma of cedar, sweat, and honey, as the mind becomes a chisel knocking holes in walls. “The song speaks of a country that I imagine, a country of my dreams, the country that little by little I am constructing,” Ferrer muses, “and of another country I am going to leave behind.”

The vivid, pulsing moments Ferrer chronicles in his songs find their way very simply and spontaneously to the studio. With minimal overdubs and a relaxed atmosphere, Ferrer and a few friends and relatives gathered regularly to lay down tracks at Ferrer’s home. “I play and sing almost everything, and usually also acted as recording engineer. My brother helped with some choruses,” Ferrer recounts. “The fundamental things we recorded live, the marimbula (bass thumb piano), cajon (wooden percussion box), bongo and clave, and the tres, the guitar, the piano. This way we avoid losing the real spirit of live music.”

This sensuous immediacy, Ferrer insists, is a requisite ingredient for changüisa and an antidote to pop fluff and folklore pedantry. “I do not accept the aesthetic dictator of the past as the present, like a sealed and invariable dogma,” he states. “We forget that much of what today has become traditional and trite, was novel at birth.” Ferrer’s freewheeling songs find this freshness and return simply to the tangible.

<< release: 03/29/11 >>

|

|

|

|

|

|