|

|

|

Down Home in Bamako:

Down Home in Bamako:

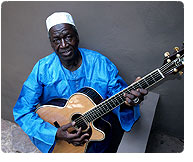

Boubacar Traoré and the Mischievously Subtle Guitar Blues of Mali Denhou

Boubacar Traoré took his guitar and strode out into the fields outside of Bamako, Mali. There, in the country quiet, he wrote a dozen new songs in a month. “Town is too noisy. And I didn’t go to the bush, but I left my guitar here, on my farm. Because I know here, I’m on a leash,” Traoré told a recent interviewer.

That leash, that connection to land and family, resulted in Mali Denhou (Lusafrica; June 14, 2011; distributed by Harmonia Mundi). On Traoré’s first studio album in six years, the kindly, gritty voice of the veteran Malian bluesman intertwines with wonderfully idiosyncratic, cascading guitar. Wistful and pensive, Traoré exhorts, gives thanks, and reflects on love, history, and duty, with a deceptive simplicity and a deep, subtle knowledge of Mandingo tradition and West African vintage pop.

A legend in Mali since his groundbreaking hits of the 1960s, Traoré—possibly the eldest internationally-touring guitarist from Mali—has been around. He knows exactly what he wants. He insisted that if he was going to do a studio album, he had to have his longtime friend, the nimble French harmonica player Vincent Bucher, play with him. Bucher’s rich, pure tone moves in and out of Traoré’s succinct phrases and unexpected rhythms effortlessly on tracks like “Mondeou.”

Traoré doesn’t fuss with his music in the studio: He’s known for whipping out one or two stunning takes and then heading back to the farm. Recorded live at Studio Moffou, the cozy recording venue designed by Malian star Salif Keita specifically for acoustic African projects, Mali Denhou beautifully presents the spirit of an African blues master, in the way vintage jazz and blues recordings captured the masters of the Mississippi Delta.

“For Boubacar, it’s not about being a virtuoso. He may only play a few notes, but they are all important,” reflects album producer and friend Christian Mousset. “Like Muddy Waters or Robert Johnson, he has a style all his own. He wasn’t taught by anyone, and doesn’t sound like anyone else in Mali. It’s always been a mystery to me, where Boubacar’s sound came from.”

~~~

An elder statesman of the Malian blues made famous by performers like the late Ali Farka Touré, Traoré is a natural. His songs and musicianship flow from an intimate, intuitive connection with his instrument, as well as with his beloved land.

As a young teenager, he would sneak into the room of his older brother—a music teacher who studied for eight years in Cuba—and play his Italian guitar. The guitar was off limits, but Traoré couldn’t help himself: He had to play. When his brother finally caught him in the act, he was amazed to hear Boubacar playing riffs taken from Mandingo music for the kora (West African traditional harp).

“When my brother found where I was hiding, he asked me, ‘Who taught you that?’” Traoré recalls. “I said, ‘No one.’ And he replied that if that was how I was starting, I was going to be world famous one day.”

Traoré continues to draw on deep roots unselfconsciously, using the legendary stories of Mali’s past, like the conversation between the king and his child retold in “Kankan Baro.” He pays tribute to Mali’s great leaders, stretching back to the great empires of the 12th century, on “Mali Tschebou,” a personal update to a long tradition of praise singing.

Songs like Traoré’s cover of a West African guitar classic, “Minuit,” show how roots and pop-influenced styles meld for the guitarist. As the lyrics contrast the prowling vampires, yowling cats, and sweetly nursing babies of midnight, Traoré navigates between fable and comforting fact, between upbeat guitar licks and a philosophical undertone.

The fame Traoré’s brother foretold came to the young Traoré in a newly independent Mali, where Traoré’s early recordings—songs like “Mali Twist” and “Cha-cha-cha 63”—became big hits and unofficial anthems of a youthful, enthusiastic nation emerging from colonialism. Though drawing on international pop dance crazes, Traoré’s songs were far from frivolous; they called on Malians to work for the good of their transformed homeland. They were played every morning on national radio; almost fulfilling the role of a national anthem. Traoré continues to remind Malians and Africans, especially those in power, to respect and dedicate themselves to their communities, in songs like “Farafina Lolo Lôra” and “Mali Denhou.”

Traoré’s star faded after his burst of pioneering success, as Mali suffered political turmoil. After returning to a quiet life, Traoré soon faced great difficulties himself: the death of his beloved wife and the harsh realities of a stint as a migrant laborer in France. But it was during this period abroad that sympathetic producers encountered the middle-aged Traoré and brought his music into the international limelight.

Traoré remains a charmingly reluctant figure on the global music scene. “He’s a country guy at heart,” muses Mousset. “He loves connecting with audiences and performing—I’ve never seen him have an off night on tour—but he’s very tied to his land and his family,” whom he greets lovingly in “N’Dianamogo.”

Though he spends as much time as possible on his farm with children and grandchildren, Traoré has calmly and confidently carved out a reputation for his straightforward sounding yet mischievously complex guitar work. “Justin Adams, Robert Plant’s guitarist who is a big admirer of African music, told me that when he first heard Boubacar, he imagined his songs would be easy to play, but he couldn’t get the groove,” Mousset recounts. “Bill Frisell also used to perform Boubacar songs, and thought his style of composition was unique. The songs seem naïve, or light, but are actually very difficult to play.”

This mix of long experience, unique style, and quiet complexity have won Traoré the respect of young Malian musicians—several joined him in the studio, adding n’goni (traditional banjo-like instrument) and balafon (traditional wooden xylophone) to Traoré’s songs.

Yet the most striking collaborator is Vincent Bucher, who first met Traoré at a festival in Canada where the two were thrown together in a jam session that blossomed into a decades-long musical friendship. Now treated as a member of the family—“Vincent is like Boubacar’s adopted son,” Mousset notes—Bucher understands how to slip seamlessly into Traoré’s guitar parts, sometimes in counterpoint and sometimes grooving right along.

Though their collaboration sounds rehearsed, it came together, like all of Traoré’s musical endeavors, with startling speed and deftness. “Boubacar is not a huge rehearser. When inspiration comes, he takes his guitar and makes music,” Mousset states. “He has his universe, his own world, and once you connect to it, it all feels incredibly easy.”

<< release: 06/14/11 >>

|

|

|

|

|

|