|

|

|

View Additional Info

View Additional Info

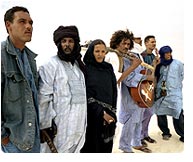

The Blue Men’s Blues:

Tinariwen Tours the USA in April 2006

Music and poetry rarely cross paths with war. For desert dwellers, poetry has long been another way of making war, just as their sword dances are a choreographic representation of real conflict. Just as the mastery of space and territory has always depended on the control of wells and water resources, words have been constantly fed and nourished with metaphors and elegies. It’s as if life in this desolate immensity forces you to quench two thirsts rather than one; that of the body and that of the soul.

With camel culture close to extinction and Mali’s peace accords of 1992 leaving a bitter taste in the mouth, the songs of Tinariwen mourn the passing of the epic golden age of the Saharan tribes, while endeavoring to map out a future for the generations who must survive beyond it and live with the modern world. After the discreet release of their first CD, The Radio Tisdas Sessions (World Village), recorded with the help of solar energy in the studios of Radio Tisdas, the Tamashek station of Kidal, their latest CD Amassakoul immobilizes their wandering music at long last. These eleven songs—released on on World Village (distributed by Harmonia Mundi USA)—mix bewitching rhythms with passionate words. They all possess that texture of something crucial, essential and honest. They are all the fruit of distress and of a hope greater than the person who expresses it, the hope of an entire community that it might once again discover its true values. That hope comes to life on American stages this April with a national tour.

Before Tinariwen, the idea of a group didn’t even exist in the southern Sahara. There were only impromptu bands who would get together for the usual joyous gatherings in camps or oases. Tuareg political figure Iyad Ag Ghali went so far as to finance the acquisition of guitars and amps for the group, and in turn used some of their songs as propaganda tools during the rebellion of the 1990s. Exile reunited these young men from Kidal, the administrative capital of the Adrar region, in the far reaches of the desert. Music soldered their talents together. This state of idleness in exile earned their whole generation the name of ishumar, after the word ‘chomeur,’ meaning ‘unemployed’ in French. The name slowly became a kind of metaphysical tag for a whole new style of songs in which the basis of existence is called constantly into question.

The tension between a glorious past and an uncertain future serves to kindle the power of words and music, whose spirit and structure will evoke, for many, the original blues, no doubt because the origin of the blues can be traced back precisely to that particular region situated near or around the massive bend of the great Niger river, where it turns south after its journey through the desert and heads towards the tropical coast of Nigeria. The blues of the Blue Men exposes strata of the history, recent and ancient, of a forgotten nation, but also reveals elements of traditional music filtered through the modernizing influence of electronic instrumentation, mainly guitars. Many guitars. This bringing together of the old and the new would probably sound wrong were it not for the fact that the personal story and destiny of each member of the group brings it’s own very real touch of exile, of tragedy and of sublimation.

In “Arouane,” Abdallah lays down the foundations of Tamashek rap to tell us how the desert is encroaching bit by bit, deep into the inner world of the individual, covering up their existence. In the authentic Saharan rock and roll number, “Oualahila Ar Tesninam,” Ibrahim dusts down the speech of the insurgent to call for the only revolt still worth the effort – that of the individual stuck in the sands of apathy and indifference. And in “Ténéré Dafeo Nickchan,” a deeply moving elegy accompanied by the tindé drum, the t’zamârt flute and an electric guitar, Ibrahim gives us goose bumps and makes us feel the meaning of asouf, that deep physical and moral sense of solitude and nostalgia that nourishes all this poetry of the dunes. As if inhabited by the presence of comrades lost in battle, of friends disappeared, of loves that have fled, this moment, along with many others on the record, makes us happy to be sad. It also leaves these questions suspended in the air. Does the soul of a fighter know peace when the bark of guns has ceased? Are the dreams of a soldier handed back along with his civilian clothes? Or do they stay mobilized on imaginary battlefields without any hope of reprieve?

(Adapted from Francis Dordor; translated by Andy Morgan.)

Additional Info

The Blue Men’s Blues:Tinariwen Tours the USA in April 2006

The Blue Men’s Blues:Tinariwen Tours the USA in April 2006

JUNE 16, 2005 UPDATE: A double blow of bad rains and locusts has ...

JUNE 16, 2005 UPDATE: A double blow of bad rains and locusts has ...

Top of Press Release

|

|

|

|

|

|