|

|

|

View Additional Info

View Additional Info

From Introspective to Global: Zemog El Gallo Bueno Subverts Santana Solos and The Doors’ Hidden Tumbao Agenda

“Even though I’m proud to be Puerto Rican, somehow it’s not fitting for me to just sing about my experiences as a citizen from there,” says Abraham Gomez-Delgado, the man behind Latin rock hybrid band Zemog El Gallo Bueno, which recently moved from Boston to NYC. “It’s much more important to use Puerto Rico as a metaphor for what is going on everywhere in the world.”

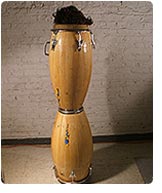

Zemog El Gallo Bueno’s upcoming CD, Cama de la Conga (The Bed of the Conga), anthropomorphizes the Latin drum, turning it on its head by putting it to bed. “People often think of hot Latin music,” jokes Gomez-Delgado, in his best Speedy Gonzales Latin stereotype voice. “I like the idea of a conga chilling out, having rest. The conga is one of the anchors of Latin music, but my music to some is backwards Latin music. So you have to see the other side of the conga. It has a life other than the nightclub. It needs to make love, be left alone, sleep and dream.”

The album is infused with questioning and protests, not only in its sometimes-abstract lyrics, but also in its instrumentation, arrangements, and band dynamics. “In the early ’90s when the term ‘world music’ emerged, it never spoke to me because it didn’t feel real,” says Gomez-Delgado. “First of all 'world music' insinuated the 'other;' something unrelated to the United States and the U.K. even though much of what is considered 'world music' was and is made in the U.S. It also felt like a ‘we-are-all-one’ utopian ideal. Of course you want everyone together and, starting at the molecular level, we are one, but by glossing over things, it becomes racist and exclusive. You’re not talking about the pain and suffering and anguish that made this folk music. I’m interested in celebrating life and culture, but I want to have the good and the ugly represented.”

Zemog (Gomez spelled backwards) El Gallo Bueno not only crosses boundaries of culture, but also of time and space. On their self-titled debut of 2003, Gomez-Delgado worked quickly and sought to create a “sonic stage” as if his very modern hybrid music was recorded in rural Puerto Rico in 1934. On his upcoming CD, he spent over a year recording and mixing, and asked his engineers to “make it sonically sound good.” And he deconstructs and reconstructs Puerto Rican and Cuban Rhythms with the rock music he grew up with to have it come back together as a new/old folkloric music.

“I remember listening to The Beatles and The Doors growing up. A lot of Doors is tumbao rockified! You can also hear Cuban influenced rhythms in the Beatles. I always liked that idea. We’ll play a cha cha cha but I like flirting with pushing it towards rock and roll, but we try to play it in just the right balance where it never quite tips into rock or fully rests in cha cha cha. Santana put rock solo guitar over Cuban rhythms. I believe this was important in the history of musics of the Americas. I would like to attempt to not just put one on top of the other but try to chemically fuse them together starting with the particles that they already have in common."

“One time my guitarist started doing a Clapton like blues riff over a mambo and it totally threw the balance off,” Gomez recalls. “He brought it to a place where it tipped the music into rock. I realized that I needed to be much clearer as to why he shouldn’t have gone there. It’s not enough just to say ‘Because I am the boss.’ I want to be able to explain that it breaks down this balance. I don’t think I need to explain my music. Music can just be music, but these issues are much more important than the music itself.”

Zemog El Gallo Bueno’s musical lifespan has gone from introspective to global. “I’ve been thinking a lot about transient people and globalization,” says Gomez. “As much as I love Puerto Rico, it can be hard to see Puerto Rico's significance in the global perspective. But if you look closer at the Puerto Rican experience through a global lens, it takes on more significance. It’s a window into the political economic soup, of who gets what and what gets who.”

The band includes musicians with roots in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, as well as European-Americans. “It’s intense to try to get everybody to understand where everybody is coming from,” Gomez explains. “I try to learn the background of Cuba, Venezuela, the Caribbean, European and African immigration as much as possible, because I see all these things playing into the dynamics of the band.

“In trying to understand that different immigrant groups had and have different treatment depending on the United States' imperialist agenda, it helps to dispel the racist myths that one group is genetically or culturally lazy while others work hard and prosper because they are of better stock. It also shows that all Latin-American groups are not 'all the same' yet they share common similarities. After World War II, industrialization and economics sent hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans to New York and Chicago, but many of them ended up living in slums,” Gomez-Delgado continues. “Puerto Rico was this showcase during the Cold War for the capitalist American colony; a showcase in opposition to Cuba, the communist showcase. Many Cubans that came over before the 1980s received millions of dollars from the U.S. government to set up businesses, because making them successful would make the U.S. look good and tell the Soviet Union to fuck off. Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico also received and keep receiving millions of dollars in federal aid while mainland Puerto Ricans comparatively received very little. So in the mainland U.S. you had Puerto Ricans living in slums, while many Cubans got straight up 'socialist style' help and in Cuba, Cubans received no U.S. help while in Puerto Rico they did: Two immigrant groups with very different treatment. And if you are from Venezuela you can’t swim over the river to the U.S.A. or take a boat. So, many immigrants from Venezuela are well-educated, well-off people, for the most part because those are the people that can afford to immigrate to the U.S.. And then the White Americans have a history of poverty and struggle with immigration. Through the years many White Americans have had a much easier time assimilating than groups of color. So for me, I have to take all those things into account. It is not about saying that all Cubans are this or all Puerto Ricans are that or even being P.C., but more about understanding what different immigrant groups have had to deal with in general under the unevenness of U.S. imperialism and embracing it through music. It is an attempt to unify by understanding differences.”

Cross-cultural differences emerge in aesthetic choices of the band. “I have been trying to understand why one culture will consider something cheesy and another will not,” explains Gomez-Delgado, whose art school training has given him a lens of critique rarely used by musicians. “I play with this one amazing guitarist who did not grow up in the United States. Sometimes he plays a straight-up Santana solo. Santana is the only Latin rock that everybody knows, and everybody wants to hear ‘Oye Como Va.’ It’s become this cliché. For me that is a musical symbol of being stuck in this stereotype. Or I play with a bass player who does a lot of slapping. I asked myself why bass slapping is cheesy to some and brilliant to others. And I realized if you take Latin music and add slap bass to it, it starts to talk about jazz fusion. When a lot of people think of jazz fusion they think of the downfall of jazz. A lot of people think smooth jazz and all the related connotations. Also many audiences want Latin music to be 'authentic'. To add slap bass somehow makes it 'unauthentic'. I equate it to wanting other countries to remain untainted by 'modernity' so they can be nice places to vacation in, yet never considering that these countries need to 'modernize' just so they can compete and survive in global capitalism.”

“Slap bass in certain places goes from being cha-cha to being a cha-cha speaking about America culture dominating. But while someone from Brooklyn might take it as a negative thing, someone from Puerto Rico might think it’s cool. My question to myself as a composer is how much of that decision do I accept in the band, looking at it from their point of view. How much more important is it for him or her making that decision than me pushing my vision conceptually.”

“What I have slowly been deciding is that small amounts of that can be very powerful, like a Rorschach test. Some of my closer mainland friends that know my music freak out. They say, ‘You can’t do that! That’s wrong!’ And some of my friends that grew up outside of the U.S. think it’s really cool. If part of my trip is to re-visit the concept of world music, then I need to consider the world and not just the people I grew up with here.”

Additional Info

From Introspective to Global: Zemog El Gallo Bueno Subverts ...

From Introspective to Global: Zemog El Gallo Bueno Subverts ...

about select songs from Cama de la Conga:

in the words of Zemog El ...

about select songs from Cama de la Conga:

in the words of Zemog El ...

Top of Press Release

|

|

|

|

|

|